Sign in for a more personalised experience

Unlock a more personalised experience to discover special offers, suggested products and more!

Sign inDon’t have an account? Click to sign up today!Still anonymous? Women in the whole History Curriculum

Thankfully, in recent decades this silencing of women in our curriculum has been actively challenged by many passionate classroom practitioners and academics. History teachers have included women that go beyond just ‘great women’ – see Susannah Boyd’s article ‘How should women’s History be included at KS3?’ – and academic scholarship now provides us with numerous rich examples of a multitude of women’s experiences and voices. My current favourite is Merry Wiesner-Hanks’ 2024 ‘Women and the Reformations’ which includes the histories of 261 named women (how many would you be able to put on your list beyond Henry VIII’s wives, Elizabeth I and Mary I?). This is alongside hundreds of thousands of unnamed women involved in the global religious transformations of the Reformations.

For most of history, Anonymous was a woman.

Virginia Woolf

However, it remains the case that despite this work, women in our history curriculum still often remain anonymous, only exceptional and silenced.

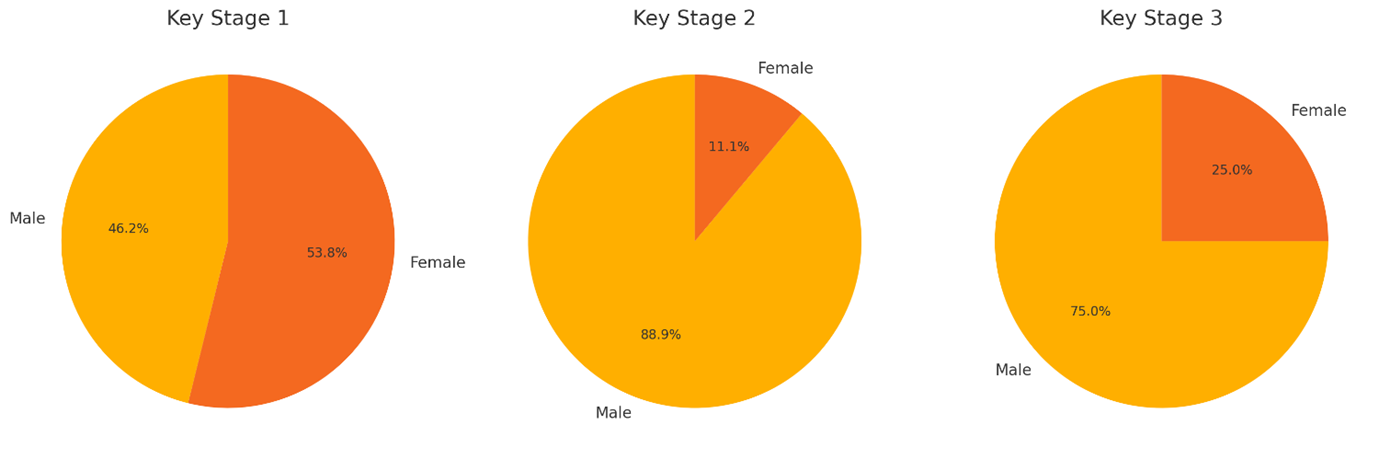

1) Anonymity remains a problem: the current national curriculum only has the following percentage of named men/women

As shown - the mention of women in History resources in the national curriculum drops away from 53.8% at KS1 to only 11.1% at KS2.

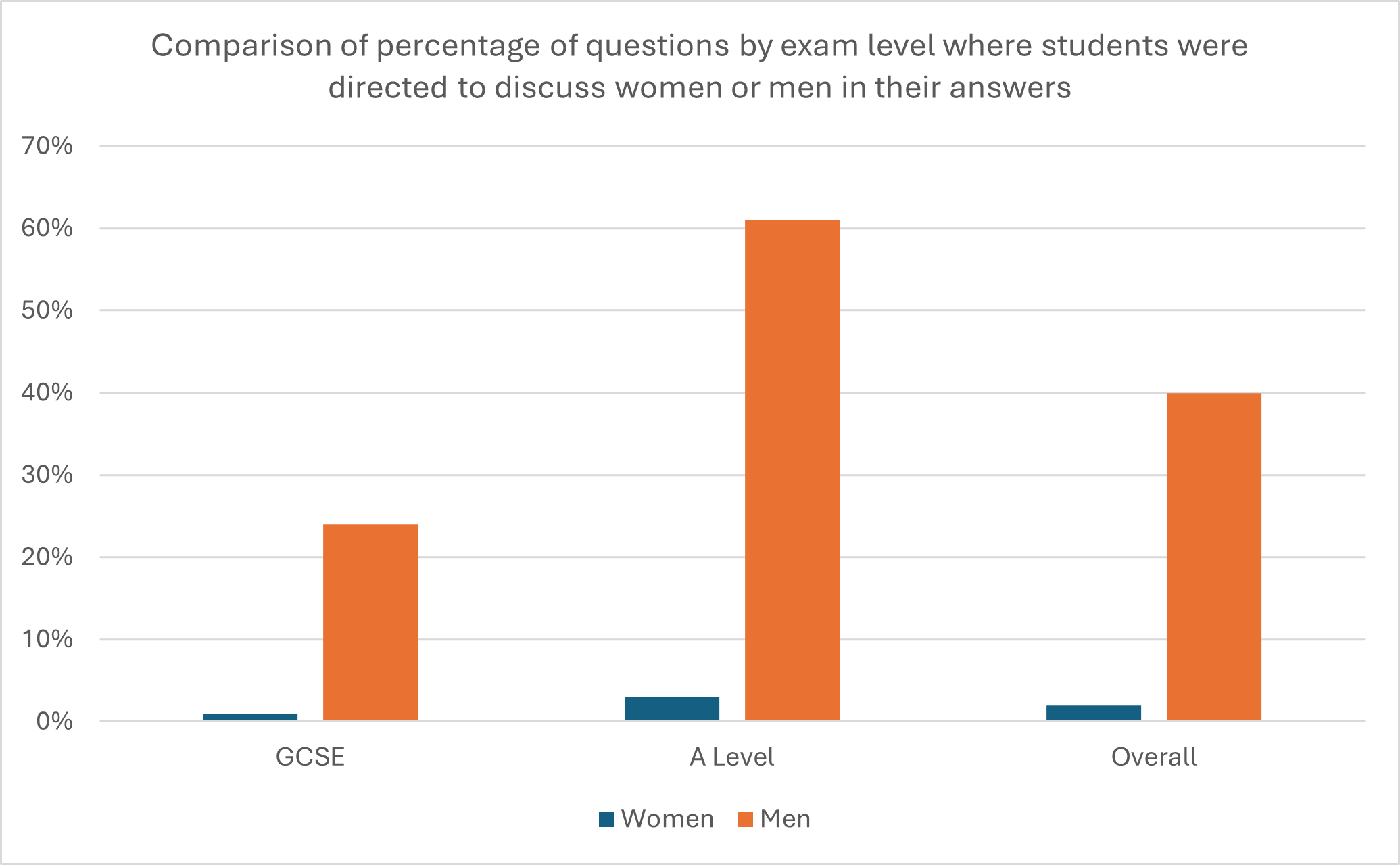

Recent A-Level exam board questions are similarly troubling:

As shown - the difference in the percentage of exam questions in which students were asked to speak about women vs men is under 5% when combining GCSE and A Level.

2) To exacerbate this, even when women are included, they are frequently only presented in exceptional roles. They are either exceptional figures such as monarchs like Elizabeth I, or they play a narrow range of roles limited to being victims and martyrs. End Sexism in Schools excellent recent report gives the full troubling picture.

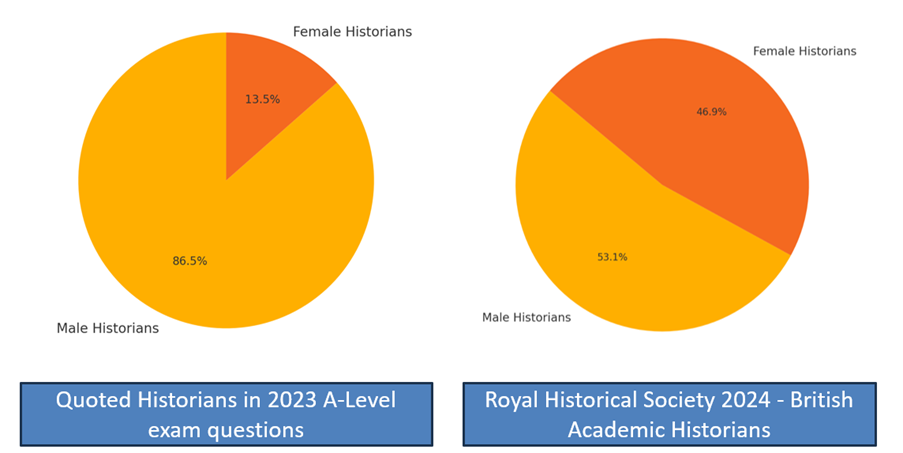

Worst of all, most women are 3) silenced as both historians and in our primary source choices. For instance, see the discrepancy below between quoted historians in A-Level exam questions against the actual % of female historians currently working in Britain.

Two graphs to highlight the difference between the number of quoted historians by sex against the number of Academic Historians that were members of the Royal Historical Society.

Women are not a minority group

It is vital to remember here that we are not speaking about a minority group. We are speaking about 50% of the population. 50% of our global past population that has been anonymised, only considered if exceptional, and most frequently silenced.

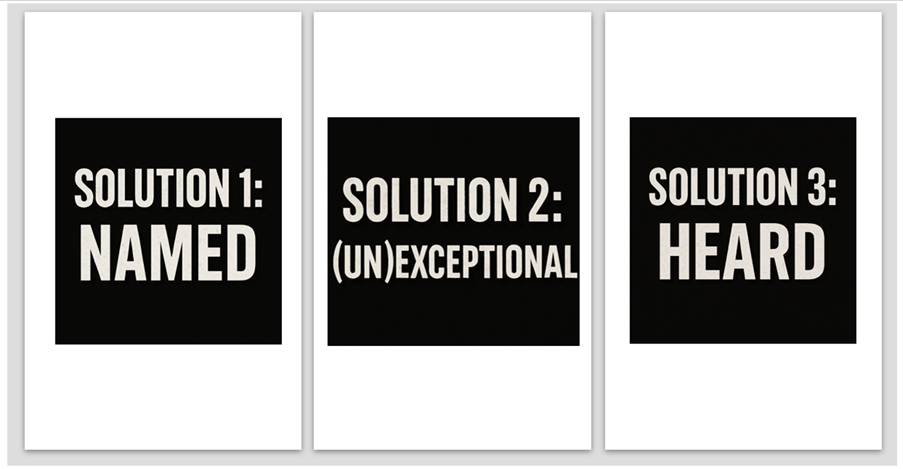

I am privileged to have worked with 20,000 girls and young women across the Girls Day School Trust– a group of schools established in 1872 to expand educational opportunities for women https://www.gdst.net/about-us/our-history/ , and we seek to lead the development of a curriculum shaped around fully including the anonymised 50%. It matters to our students that women are named; it matters to them that they see a multiplicity of women’s roles that are (un)exceptional; and it matters to them that women are heard. If we don’t do this, at best we present a grossly inaccurate depiction of the past and at worse we are active participants in perpetuating the silencing of women’s voices.

If we don’t do this, at best we present a grossly inaccurate depiction of the past and at worse we are active participants in perpetuating the silencing of women’s voices.

How Changing Histories is helping to address the issue

It’s for these reasons that it is hard not to get excited when textbooks are produced that provide time-poor teachers with resources that name women, provide stories of both the exceptional and unexceptional, and allow women’s voices to be heard. The Changing Histories series seeks to address all three of these issues. The first in the series, Connected Worlds, opens with Empress Zoe in Constantinople surveying her Byzantine Empire. Saint Foy and her relic serves as a window into understanding Western Christendom. There are also enquiries on Eleanor of Aquitaine and renaissance painter Sofonisba Anguissola. Alongside the more exceptional, we see villagers Agnes and Julia in the account of the Black Death in Walsham. Or we hear of how the Reformation impacts the lives of Margery Lake and ‘Old Joan’ in Morebath. In addition, historians Claire Kennan, Helen Castor and Miranda Kauffmann and archaeologist Sabine Hyland are integral to the research methods and are also presented through video content on the Boost platform.

The more recently released, Changing Histories - Expanding Worlds continues this approach. It opens with histories such as Anne of Denmark’s giving a fuller understanding of the Stuart world. Whole enquiries now focus on significant women such as Nur Jahan. Also watch out for:

• Anne Hutchinson in the Puritanism chapter

• Henrietta Howard in the transatlantic trade chapter

• Weetamoo in the American colonies chapter

• Betty Johnstone in the experience of empire chapter

• Elizabeth Prowse in the agricultural revolution chapter

• Anne Lister in the industrial revolution chapter

• Mary Wollstonecraft in the Enlightenment chapter

• ‘Nanny’ in the Jamaica chapter

• Harriet Arbuthnot in the 1832 Reform Act chapter

• Elizabeth Fry in the Reform from above chapter

Even more important than these named “exceptional” individuals are the numerous women whose stories are woven into and embedded in the enquiry questions. For instance, we meet Betty Shaw and her three daughters and learn how to access their hidden voices and experiences of industrialisation. In an earlier chapter, we hear a reconstruction of oral histories that shed light on West African women’s medicinal use of African Mahogany. These resources actively demonstrate that women are of significance and worthy of study in connection with all aspects of the past.

Finally, the textbook also exemplifies that women’s voices are integral in the writing of history. The textbook champions the work of female historians such as Ruby Lal and Emma Griffin. This is crucial. I’m convinced it is primarily as historians that students can most readily “see themselves” in our curriculum.

The contents of the third book in the series, Fragile Worlds remain a closely guarded secret, but to whet our appetites, I am informed that teachers and students will hear the stories of many more named and (un)exceptional women such as Gelya Markizova, Hanah Mitchell and Lien de Jong. Individual lives that I will leave you to investigate further.

It is this multi-dimensional approach to including women’s voices and experiences that we all need to embrace if our curriculum is going to convey an accurate depiction of the past to our students. Let me end with one of my student’s voices when I asked them in their final lesson of year 13 how they wanted to see women’s history included in the curriculum.

“Even though studying women's history separately would provide a unique platform to elevate female stories and help us understand how the female experience differed, I believe that this would have the adverse effect of making women a sub-section of history. Would it not imply that 'regular' history is reserved for men? Women's experiences are not an isolated category, their stories influenced and were connected to every aspect of the past.”

Go on - embed women in your whole curriculum.

Jake Unwin - Director of Progress at Sutton High School (GDST)

Changing Histories - Shining a light on Women in History

Hear from us

Curriculum changes. New materials. Price discounts and unmissable offers. We’ll make sure you don’t miss a thing with regular email updates, tailored by subject and age group.